A history of Australia at the World Cup

The story of the Socceroos and the World Cup is one of triumph and despair. We chart the story across the years

Brazil, in the old joke, is the country of the future – and always will be. For years football has been Australia’s sporting equivalent of Brazil – almost there, about to happen, on the cusp of something wonderful, then finally resolving into nothingness, a behemoth only in the imagination of its own promise. Nothing illustrates this better than Australia’s legendary history of under-achievement at the World Cup. It’s a marvel Australia are there at all because for years after the landmark of 1974, it looked like the team would never make it, or never make it again, great peaks of anticipation around each qualifying tournament giving way to valleys of years-long disappointment, the game’s sense of itself and of its rightful place in the national sporting firmament colliding with hard reality in ways that served for decades to nourish a burning sense of recrimination, and entitlement, and misplaced hubris, among those who run and cherish the sport in the country.

Football, more than any other sport, has always been a reflection of the human movements that have shaped Australia’s post-settlement history

Football, more than any other sport, has always been a reflection of the human movements that have shaped Australia’s post-settlement history; each wave of immigration has given the game renewed impetus, and renewed sources of friction. The earliest mention of football in Australia dates to 1832, a letter writer to the Sydney Herald referring disparagingly to “a large batch of youngsters” idling away their time playing football in Hyde Park amid a tableau of “drunkards”, “disgraceful pitched battles”, unmotivated constables and “wretches” lying in ambush in the park’s thickets. Later references, from the 1870s, involve contests that reflect, however glancingly, the fragility of public order in the southern colonies: Melbourne club take on “The Police”, Brisbane club travel to Woogaroo asylum to confront an ad hoc team of psychiatric inmates.

Delirium, contested authority and the sense of an order at permanent risk of giving way: these were the originary themes of the Australian football experience, and so it has proved with the country's participation in the World Cup, too. Australia has had clubs and formal state-based football associations for well over 100 years. Sydney clubs were the first in the world to adopt numbering of players, in 1912, and the first national association was formed in 1921. Tours by Hong Kong, New Zealand, and India (whose team played in bare feet) through the interwar years attracted some attention, but distance, loyalty to Britain (which had withdrawn from Fifa in a huff in 1920) and perhaps the most telling factor of all – not being invited in the first place – meant Australia was well out of contention for the earliest World Cups until after the Second World War.

Earlier spikes of enthusiasm for the game in Australia had been driven by recent arrivals from England, but it was mass migration from southern Europe after the war that gave Australian football its most lasting, defining shock. Australia at the time was a proudly xenophobic place. As new, “migrant” clubs sprouted in the inner suburbs of the main capital cities, the Australian Soccer Association – an Anglo affair – began to fear a kind of racial encirclement. Time and time again the migrant clubs lobbied to be allowed to join the association so as to compete with the established district clubs, like Cessnock and Balgownie and Corrimal and Granville; time and time again they were rebuffed.

This was the era where football came to be viewed as the fluffy pursuit of “sheilas, wogs and poofters”, the phrase made famous by Johnny Warren, eventually becoming – by accident more than design – the stage for some of postwar Australia’s grandest, most theatrical jealousies, insecurities and fears. Frustrated at the perceived injustice of their treatment, the immigrant clubs eventually formed a breakaway federation; a bureaucratic rope-a-dope followed which eventually resulted in Fifa suspending all of Australia’s feuding football federations indefinitely.

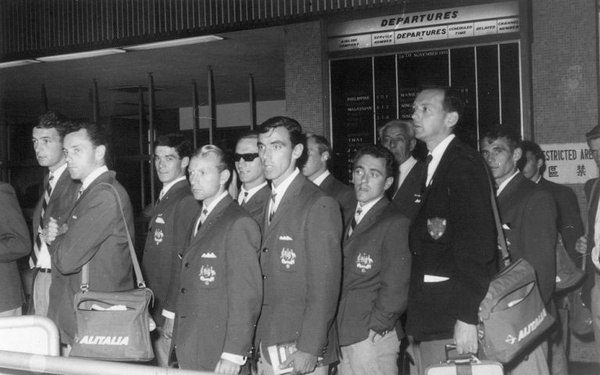

The wogs’ revenge came in 1963, with the “migrant” Australian Soccer Federation wresting control of the game away from the Australian Soccer Association, making peace with Fifa, and preparing the national team’s first real assault on World Cup qualification. Australia was thrown in with the Asian confederation and in 1965 faced a two-leg playoff against North Korea in the neutral venue of Phnom Penh for the final place at England’s “home” World Cup. Australian football at that point was very much an amateur pursuit; the squad, composed entirely of part-timers, met for a training camp at the Cairns YMCA prior to boarding the flight for Phnom Penh, each member receiving $5 a day for his labours. True, a modern incentive scheme was taking shape, but it was laughably rudimentary: on a later tour to Vietnam, Australia’s players were told that each of them would be able to keep his tracksuit if the team won.

North Korea, meanwhile, were a crack outfit of highly skilled full-time professionals. Not for the first time Australia seriously underestimated an Asian opponent. The team sailed blithely into Cambodia utterly unprepared for the shock of playing overseas, before 60,000 people, in a strange and overwhelming city. A 9-2 aggregate thrashing followed, Australia’s humiliation serving as a mere staging post in the rise of North Korea, who once in England would famously go on to beat Italy 1-0 and take a 3-0 lead within the first half-hour of their quarter-final against Eusebio’s Portugal. Les Scheinflug’s two goals and the formation of a national team nucleus around Warren and Ray Baartz were the only consolations of an introduction to World Cup football that was mercilessly fist-to-mouth. “When we arrived in Cambodia it was literally like arriving on another planet,” Warren wrote in Sheilas, Wogs and Poofters. “We were completely out of our depth.” Australia was to remain that way for some years to come.

Through Australia’s World Cup wilderness years it was often argued that one of the biggest things holding the Socceroos’progress back was their position as the sole heavyweight in a region – Oceania – which, in global football terms, was insignificant to the point of invisibility. We needed to be in Asia, it was said; we needed longer and more testing qualification campaigns against higher-quality opponents, not the flash fry of sudden death against South America’s battle-taut fifth-best side; there was no hope of national progress as long as rote thrashings of Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands remained the staple diet.

Australia’s admission to the Asian Football Confederation in 2005 is widely seen as the administrative coup de grace that set the nation’s footballing destiny back on its rightful path, handing the Socceroos – at long last – the things it had always been searching for: skilled opposition, regular contests, transcontinental travel and togetherness, the accoutrements of the normal footballing nation. But Australia’s move to Asia was no new thing. On the contrary, 2005 represented the reassertion of a former order, more a return to Asia than a reluctant, won-over embrace of it, because for much of the national team’s early World Cup history, the neighbours to the north were at the very centre of Australia's qualification hopes, with elaborate, testing, multi-part campaigns more the norm than the exception.

The campaign for the 1970 World Cup was a case in point. Victory over Japan – bronze medallists at the 1968 Olympics – and South Korea in a round robin tournament gave Australia the chance to play first Rhodesia, then Israel, to win a place at Mexico ’70. This was the era of apartheid and boycotts, the Cold War and decolonisation reverberating through world sport and creating an atmosphere of intense politicization around seemingly every football international: Australia was forced to play Rhodesia in Mozambique, the Portuguese colony chosen as the venue because Portugal was the only country that would allow the pariah, white-ruled state to play on its territory.

The Australians needed three matches but eventually accounted for Rhodesia. From Mozambique the team traveled directly, for 36 hours, via Lisbon, Rome, and Athens, to Tel Aviv. Twenty-four hours after landing they lost the first leg 1-0 to Israel, before returning to Australia where, despite dominating the opening 70 minutes of the return leg at the Sydney Sports Ground, they promptly stumbled to a 1-1 draw. The Israelis advanced to Mexico, while each Australian player, as reward for his participation in the four-month qualification campaign, received $13.27. The agony of the near-miss was rapidly becoming a lead theme of Australia’s World Cup experience.

By 1972 the team had been given the nickname “the Socceroos” by the Daily Mirror’s chief football writer Tony Horstead. The name might grate today, degenerating as it has into little more than a rhetorical hackysack that gets kicked from side to side in the world’s most tiresome debate – whether Australians should call association football “soccer” or “football”. But at the time it was quick, and catchy, and clever, and gave the team something that football’s marginal status in Australia meant it desperately needed: a marketable identity, and one which tapped into the innate Australian need to see kangaroos do things humans might do (play football, box).

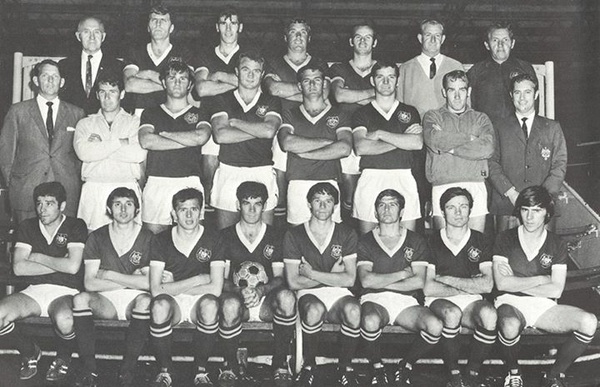

A young new coach had been put in place, too, and he was not a man to be messed with. Rale Rasic brought a fresh spirit of discipline and innovation to the team, demanding his part-time squad of tradies, security guards and milkmen train with the rigour and application of full-timers and calling on the services of a sports psychologist to motivate them. There was also a kind of antic, steaming fury to the man – precisely the kind of energy that dozy, down-there, good-enough Australia needed to finally shuffle off its footballing torpor and secure passage to its inaugural World Cup.

As for 1970, the story of qualification for 1974 had a decidedly Asian complexion: victory over Iran, the away leg being played before 130,000 in Tehran’s newly constructed Azadi Stadium, gave the Socceroos the opportunity to face off against South Korea for the final place in West Germany. Two draws, in an era before the away goals rule was born, created the need for a third match to decide the tie; Australia traveled to Hong Kong and pulled off a 1-0 victory. The winning goal was a thing of rare beauty, a lofted ball into the area bobbing off the head of a Korean defender before Socceroo midfielder Jimmy Mackay, lurking 25 yards from goal, stepped forward and hammered the ball into the top corner. Few goals in Australia’s history have been as pretty; none, arguably, has been as significant.

Australia were expected to do little at the 1974 World Cup, and they broadly complied, comfortably finishing at the foot of their group. But losses to East Germany (2-0) and West Germany (3-0) were narrower than predicted, and a draw in the torrential rain at Berlin’s Olympic stadium was enough to give the Socceroos their first ever World Cup point. Striker Adrian “Noddy” Alston’s surprisingly spiky duel with Franz Beckenbauer in the match against the eventual champions drew faintly patronising praise from the German media; the tabloid Bild, which had branded the Socceroos “no-hopers” and “greenhorns” in the lead-up to the tournament, was moved to print a formal apology once the group stage concluded. “We were wrong,” the paper stated. “The Australians have been a wonderful squad. Goodbye and good luck, Aussies.”

Australia, a team of odd-jobbers into football purely for fun, had qualified for the sport’s pre-eminent professional tournament at just the third attempt

It was, on any reading, a magnificent achievement: Australia, a team of odd-jobbers into football purely for fun, had qualified for the sport’s pre-eminent professional tournament at just the third attempt. The condescension of the European football media was a minor irritant, a prejudice to be endured with humility and quickly banished on the field of play. A bright future for Australia at the World Cup, surely, beckoned.

The tonic of 1974 imbued Australian football with a new sense of purpose and energy. Club owners such as Alex Pongrass at St George and Frank Lowy at Hakoah led the push to create the National Soccer League, a visionary concept for a country in which states still ran discrete competitions in each of the other football codes and there were few meaningful outlets for intercity sporting rivalry. The league started brightly but tensions between different state associations and their leading potentates quickly surfaced, and before long the competition was lurching from format to format and season to season: knock-out finals series, a first-past-the-post system, split conferences, a reconsolidated single division, winter and summer were all given a go, with varying degrees of failure. This captured the central malaise of Australian football in the barren years, the three decades of frustration and stagnation that separated that first bijou of 1974 from the coronation of 2006: incompetent administration.

Other major themes were taking shape at the time as well: the increasing professionalisation of the sport, the club-versus-country controversy, and the perceived injustice of the country's treatment at the hands of Fifa, which at each sudden death stage continued to boot Australia, the half-placers of Oceania, from region to region with the carefree malevolence of Blofeld stroking his cat.

Many in the Australian football community would wage a campaign to rid the local game of what they saw as the corrosive influence of “Pommy bastards”

But as Australia prepared to mount its follow-up assault on the World Cup, in 1978, an entirely different issue flared. After West Germany, Rasic was given the boot and Englishman Brian Green took his place. Green soon quit over a shoplifting offence and the position was thrown open to a poll of the state members of the Australian Soccer Federation. The vote, overlaid with all the factionalism and pettifoggery that blighted Australian football through the final decades of the 20th century, eventually saw Jimmy Shoulder, a 28-year-old Englishman with virtually no coaching experience, ascend to the top role. The Socceroos tumbled out of a qualification group including Iran, Kuwait and South Korea, and much of the blame fell, with little justification, on Shoulder. For much of the following 20 years, many in the Australian football community would wage a campaign to rid the local game of what they saw as the corrosive influence of “Pommy bastards”. Like much else in the national game at the time, the campaign was impassioned, dedicated – and an extravagant waste of energy.

The 1980s, in keeping with this spirit, were a rumbling, jazz-hands shambles of a decade in Australian football, the undoubted nadir coming when the national youth team, drawn to play Mexico at the Azteca Stadium, underestimated Mexico City’s traffic and arrived for the game an hour late. The campaign for 1982 was lost to New Zealand; Sir Alex Ferguson’s Scotland became the immovable obstacle in the quest to qualify for Mexico ’86.

But things brightened towards the end of the decade. If nothing else there were goals to get excited about: Charlie Yankos’s free kick against Argentina in the 1988 Gold Cup, Frank Farina’s strike against Yugoslavia in Australia’s opening group game at the Seoul Olympics, and Ned Zelic’s double against the Dutch to qualify for the same tournament four years later. Zelic’s goals in particular – the first scored on the counter, the second struck from an impossibly acute angle in the dying minutes, both carved from the null space in which Australia’s famously vomitous 1992-era strip was designed – left a lasting impression on the public at a time when TV and sport were tiptoeing towards a more earnest economic commitment to each other.

Meanwhile the twin forces of commercialisation and internationalisation were sweeping through the major overseas leagues and a steady trickle of our most talented players, from Mark Bosnich to Robbie Slater, had begun to infiltrate the top-tier clubs of England and Italy. But with each World Cup qualification campaign, the parade of sad carried on. A loss to New Zealand killed Australia's chances of making Italia ’90, and despite the penalty-saving heroics of Mark Schwarzer against Canada in the preliminary qualification hurdle for USA ’94, the Socceroos were unable to squeeze past Diego Maradona’s Argentina in the sudden death play-off that followed. Advances by Australia’s national teams in other sports – most notably rugby and cricket – had given the public a taste for conquest. Football was beginning to look decidedly backward, less a poor cousin to the other football codes than their stunted, forgotten childhood friend.

The mid-90s saw the sport get more serious, the gabby, glad-handling new head of the now-rebranded Soccer Australia, David Hill, bringing a touch of marketing shazam to a previously moribund national body. Hill’s boldest stroke, alongside his attempt to “de-ethnicise” the national league, was to throw the keys of the national team to the first of its high-profile foreign saviours: Terry Venables. The Pommy bastards were back.

Venables wore a grin as permanent as his tan during his brief stint with the Socceroos, and a gifted squad, including Craig Foster, Alex Tobin, Stan Lazaridis, and a teenage Harry Kewell, seemed to respond well to his tutelage. This was the dawn of Kewell’s golden age, a time when his accent still bore a faint trace of its first decade-and-a-half in Sydney, public goodwill was abundant, and the world was starting to awake to the skill and potential in those splayfoot bandicoot legs. The later symptoms of decline, from season-long stints on the Liverpool bench to interviews with Ray Martin, were still well in the distance. To watch the young Kewell in action over the November 1997 play-off against Iran, hypnotically travelling up and through the registers of an off-the-ball-run with the practised ease of a master playing scales at his piano, was to witness the first stirrings of a talent unlike anything Australian football had seen before.

Everything else about that wrenching, final leg at the MCG, however, Australian football was already well familiar with, the rush of legitimate pre-match expectation and the euphoria of Kewell’s opening goal sundance giving way, inevitably, to petrified defence and the dagger-strike of Ali Daei’s masterly through ball. By full-time Australia was a tableau of national distress: Graham Arnold slumped on the turf, Johnny Warren in tears on SBS. Iran '97, truly, was Australian football’s cruellest cut, sending the game into a funk from which it took a full half-decade to emerge.

When the next qualification loss rolled around in 2001, home-and-away to the fabulously round Victor Pua’s Uruguay, the nation’s disappointment seemed less raw and more rote, as if we were recognising the dull return of some prior trauma. Uruguay, the team of Alvaro Recoba and Dario Silva, were a magnificent outfit, it’s true; but so were the Socceroos, led by Paul Okon and illuminated by the contrasting talents of Kewell and Mark Viduka. The real problem with the Australian squad was a lack of togetherness, the preening of its brighter lights and insecurity of the rest contributing to a general poisoning of squad morale. One story, reported in the Sun Herald at the time, claimed that over the course of his entire time in camp with the Socceroos, Kewell deigned to address his team-mates on just one occasion. “Pass the salt,” he is reported to have asked his neighbour at lunch one day. By 2001 the Australian public had become a little like Kewell at the lunch table in their consumption of the Socceroos’ World Cup campaigns: impassive, glazed, and numb to human feeling.

It was as if after Iran '97, all the progress made through the Hill years, the macho noises and the flash bulbs of ambition, instantly flickered out. Pass the salt.

At 1-0 down after the first, away leg against – that team again – Uruguay in 2005, familiar agonies returned. True, Australian football had made confident strides in the years since the deflation of 2001. The government-commissioned Crawford Report had signed the death warrant of the old NSL, a new football federation was formed, and Frank Lowy, the sage of Bondi Junction, Australian sport’s answer to Warren Buffett, took the reins of the game and put in place the beginnings of a technocratic, commercially focused order, luring John O’Neill away from the ARU in a signal gesture of Australian football’s shift into the mainstream. After years of misadministration, the game was in the early throes of a new sobriety.

The coaching set-up had also been revolutionised, Guus Hiddink enlisted after the Confederations Cup debacle of mid-2005 to replace Frank Farina and mount a daring late dash on qualification for Germany. Hiddink was the Socceroos’ lucky charm leading into 2006. Everything about the man, his stature in the world game, his stubby authority, his very Dutchness – carrying, as it did, the faintly thrilling suggestion of fluid, inventive, Total Football – gave the nation reason to believe that This Time Would Be Different.

One swoop of Aloisi’s left leg put an end to the indignities of the previous 32 years. Australia had come home from the desert.

But Australian football had experienced dawns before; they’d all turned out to be false. One-nil was a slim lead for the Uruguayans to carry into Sydney but everything about the Socceroos’ history contrived to make it look enormous; and when it arrived, the equaliser, put away by Mark Bresciano after a snatching goalmouth scramble, captured the anxiety of the team, and the football community, and the nation more generally. Then came extra time; then came penalties; then came Schwarzer. John Aloisi, and delirium, followed. The night of 16 November 2005 was immediately catapulted into the pantheon of Australian sport’s very best moments, right up there with Australia II and Cathy Freeman’s gold in the 2000 Olympics, speaking as it did to easy themes of pain and redemption and multi-ethnic national becoming. One swoop of Aloisi’s left leg put an end to the indignities of the previous 32 years. Australia had come home from the desert.

This was Australia’s rabona generation, a squad composed of maximum wattage talents. Schwarzer kept an ungenerous stall in goal; Lucas Neill gave the back four its animating rage; the composure and diffidence of Bresciano and Vince Grella in midfield played off against the hustling, happy chappy endeavour of Tim Cahill and Scott Chipperfield; Kewell supplied the required touch of Kewell-ness in the hole; and at the apex of the formation stood captain Viduka, a striker gifted with volume, delicacy of touch, and the efficient lethargy of Romario at his best. Lost in the avalanche of national outrage following Fabio Grosso’s “dive”, the moment that would end Australia’s 2006 World Cup dream after the stunning comeback against Japan and draw with Croatia had put the Socceroos into the second round, was recognition of the fact that a squad of this quality, playing against 10 men for much of the second half following Marco Materazzi’s 50th minute dismissal, should have made their advantage count.

A second round exit to the eventual champions was no disgrace, of course; and the Socceroos, in 2006, unquestionably gave the Australian game the turbo-lift it had been waiting half a century for. Cahill attacking the corner flags in the Kaiserslautern sun, Dario Srna poised darkly over the ball as he lined up the free kick that would give Croatia their early lead, Kewell’s leap on scoring the equaliser, Graham Poll with his three yellow cards: Germany 2006 was a tournament in which every still, every photo, every moment seemed to bear the weight of some greater historical significance. One image from the qualification win over Uruguay spoke louder than others, however: the tableau of Australia’s players, led by Tony Vidmar, rushing towards Aloisi after he struck the winning spot kick. But the real focus of the image is Kewell, his pose – arms outstretched, face a picture less of celebration than self-congratulation – expressing a kind of lightly entitled hubris. The hubris, of course, was not Kewell’s alone; it took hold of much of the rest of the Australian football community in the aftermath of 2006, spilling over into a flood of apocalyptic proclamations about the sport’s potential in Australia. We were on the map! The giant had awoken! The future belonged to football!

The Socceroos, finally cut free from Oceania and newly welcomed into the Asian Football Confederation, travelled to the 2007 Asian Cup with renewed belief in the destiny of Australian football, but a disastrous start saw them exit on penalties to Japan in the quarter-finals. The re-entry to normal life after the euphoria of 2006 was rude; a major correction of expectations followed. The paranoia of the Graham Arnold interregnum gave way to the Pim Verbeek era, and the debates at the heart of the national footballing conversation took on dimensions of new detail and complexity. The big question was not so much whether we would make the World Cup at all as how strongly represented A-League players would be in the final squad and whether we really needed that many defensive midfielders.

Verbeek had all the gruffness of Hiddink, with none of his man management ability, commitment to attacking football, or tactical acumen. The horror opening day 4-0 defeat in 2010 to the jumping castle of a side that was Joachim Low’s Germany brought down the curtain on the Socceroos’ rabona generation. Kewell’s dismissal in the second game against Ghana (“What? Me?”) deepened the disaster and even though some pride was salvaged in the victory over Serbia, lit up by Brett Holman’s long-range screamer, the sense prevailed that the early ecstasies had run their course. After the breakthrough of 2006 and the sideways step of South Africa, what Australian football needed, once more, was a simple shock of the new.

Osieck’s appointment was greeted with an enthusiasm reminiscent of the collision of two sheets of wet lettuce;

What it got, instead, was more of the same, new coach Holger Osieck persisting with the stars of 2010 and 2006 even as they began to move into the rainshadow of their careers. Osieck’s appointment was greeted with an enthusiasm reminiscent of the collision of two sheets of wet lettuce; after the safety-first mentality and tone-deafness of the Verbeek era (“I think we had more difficult weeks during our World Cup qualification, to be honest,” was the Dutchman’s reaction to the 4-0 thrashing against Germany), the footballing public yearned for an innovator true to the legacy of Rasic and Hiddink. Names like Frank Rijkaard, Marcelo Bielsa and Philippe Troussier were thrown about. Instead, we got a bland journeyman in an ill-fitting suit whose sole contribution of any interest to the national conversation was to tell a “joke” about the need for women to shut up in public.

Asian experience was Osieck’s big draw, the German having coached Urawa Red Diamonds to the AFC Champions League title in 2007. Initially this brought encouraging, unexpected success. After the disaster of the previous campaign, expectations for the 2011 Asian Cup were, it’s fair to say, kept on a very low heat. Defying the pessimists, the Socceroos recaptured some of their 2006-vintage fizz to scythe through Uzbekistan in the semi-finals before falling, narrowly, to Japan in the final.

But early results in the World Cup qualifiers were underwhelming, and as the Socceroos, oddly one-step and clinging, with a tenacity beginning to verge on desperation, to the class of 2006, puddled to a shock loss against Jordan, the fear of missing out on Brazil altogether lurched into view. Josh Kennedy’s header under the Sydney rain was enough to banish that fear, but by that point the Osieck era had devolved into a dull thrash of competing resentments and hostilities: why was the German not placing more trust in the younger generation? What was the long-term development plan when players such as Tom Rogic, Nikita Rukavytsya, Tomi Juric, Massimo Luongo, Tommy Oar, and James Troisi were not being given a proper shot at establishing themselves? Where was the commitment to the simple business of scoring goals? And why had the task of root-and-branch rebuilding of the national team been entrusted to a foreigner – the old xenophobia peering above the parapet once more – of little achievement when local coaches had at last begun to flourish in the A-League?

Ange Postecoglou’s appointment, following the double-sting of successive 6-0 humiliations to Brazil and France last year, has, for now at least, locked that last question away. But the transition to a new generation remains a work in progress, as does the quest for a durable national team style built on mobility, and pressing, and ingenuity, and touch. The expectations of the broader public, which also arguably played a part in the slow decomposition of Osieck’s hold on the job, remain as outsized as ever. Many Australian football supporters, perhaps affected by the outrageous successes of their national teams in other sports, have always fancied the Socceroos as a Selecao-in-waiting. Our country is a clean-skied paradise of outdoorsiness and rude physical health; of course we should be winning the World Cup. Despite the depth of the back catalogue, correctives to that self-perception – and the 2014 qualification campaign supplied many – are still met with disbelief.

There’s nothing wrong with ambition, of course: progress, quite rightly, has fed the desire for greater progress. But three World Cups on the trot for a nation previously accustomed to a quadrennial diet of despair are no small achievement, especially given the depth of competition for talent across the different codes. The game has made greater advances over the last decade than in the previous three. Football, to rework the joke about Brazil, may yet be the sport of Australia’s future – but for now, it’s claiming an ever-growing share of its present. If we’re honest with ourselves, few of us who lived through the 1990s thought we’d get here so quickly.

Credits

- Words

- Aaron Timms

- Editors

- Tom Lutz, Madhvi Pankhania

- Pictures

- Jonny Weeks, Steve Bloor, Daniel Kirkwood

- Archive

- Tom Jenkins, Getty Images, AFP, AAP, AP, Corbis, Johnny Warren Community Page