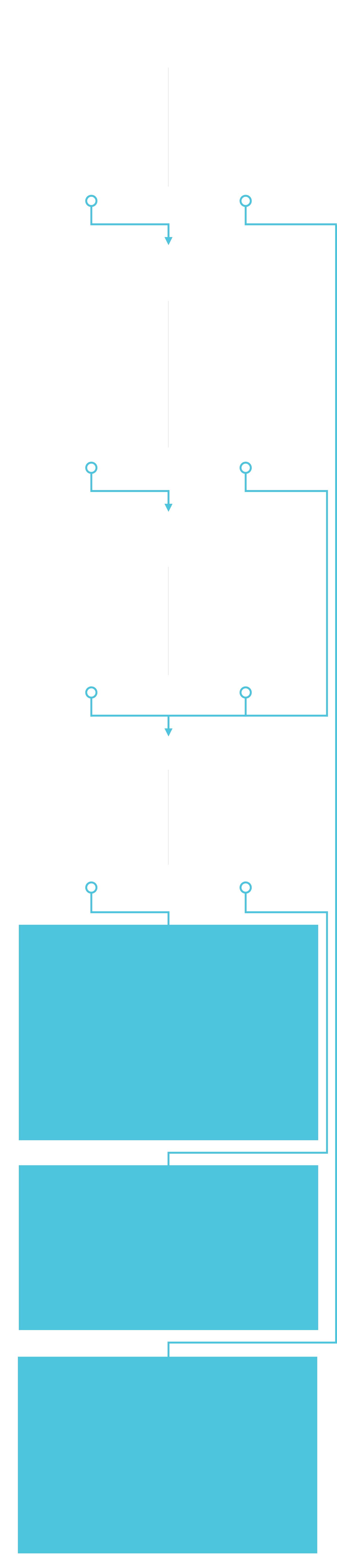

Syriza finds itself unwilling or unable to force through a debt reduction

Both Athens and Brussels hold firm > Expulsion?

Greece exits the euro and breaches the one-for-all symbol of European unity. Dismay on the streets of Athens. The financial markets panic and look to other countries that could threaten to quit. Spain, under pressure from a secessionist party in Catalonia and the anti-EU Podemos party, could face a run on its debt. A panic could trigger another Brussels rescue operation.

Greece holds firm > Brussels is lenient > Dominoes

Greece takes an uncompromising stance which Brussels reluctantly accepts. Ireland and Portugal ask for the same treatment. Spain’s anti-austerity party Podemos grows in strength. The euro falls in value. Sterling rises, leading to trouble for British exporters. Ukip laps it up, but it comes at the worst possible time for the other UK parties going into an election. Labour would suffer from associations with high-spending, high-debt social democratic countries. The Tories would be associated with austerity and its side-effects.

If Syriza backs down, the consequences are likely to be felt more in Athens than in Brussels, at least initially. Greece has backed down before, which caused riots in the streets and a near breakdown of civil society. Elected politicians would come under pressure from the army to regain control. Prolonged rioting almost brought the generals back in 2012; it could be repeated in 2015.

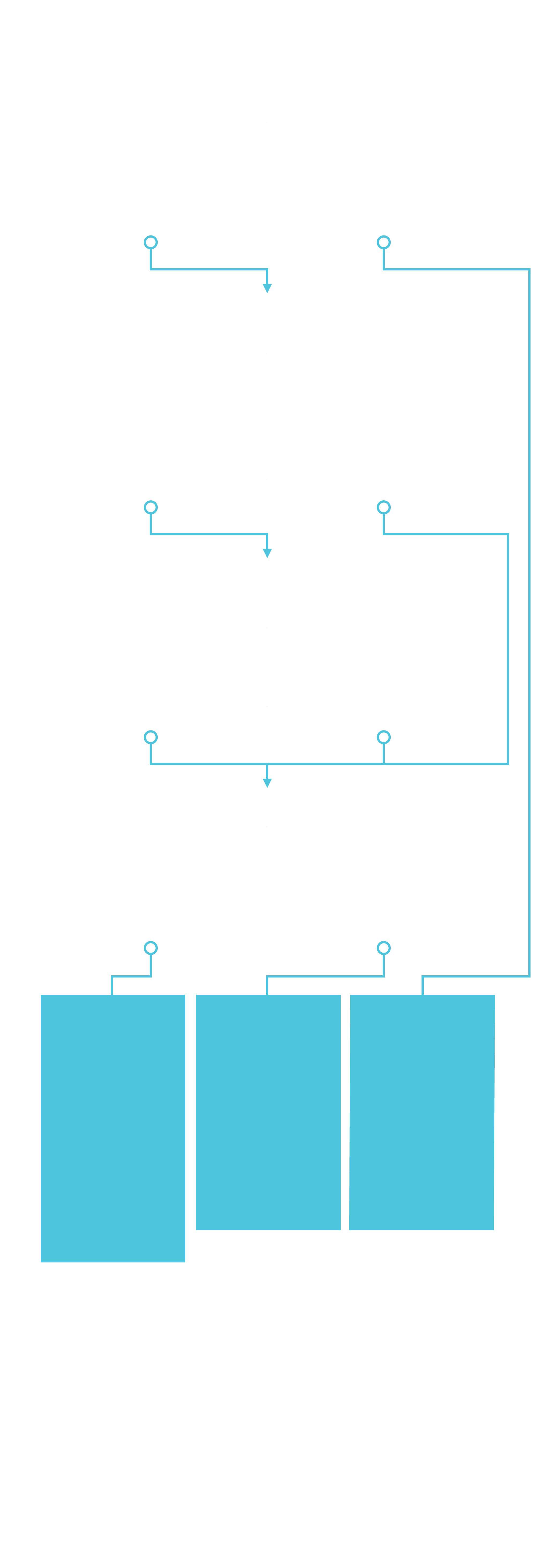

Will Syriza try to reduce debt and keep the euro?

How could Greece stay in the euro and renegotiate its debt?

How could Brussels react?

OPTION 1 The EU can accommodate Greece in a number of ways, either with a fudged solution which satisfies Greece without a default, or by consenting to a default, in one form or another. In any of these scenarios, though, there will be further interested parties.

OPTION 2 If Greece defies Brussels, by leaving the euro and redenominating its debt, or by defaulting, Brussels may feel obliged to impose sanctions, the ultimate of which is probably expulsion from the EU. But there is no mechanism for this.

OPTION 1 Greece tries to secure a negotiated agreement on its debt within the EU. Brussels will probably counter by trying to convince Greece to honour its debt, but may have to provide incentives for Greece to do so, either in debt restructuring or in increased EU funding or both.

OPTION 2 Greece unilaterally defaults on a slice of its debts, but says it will stay in the single currency. It challenges Brussels to kick the country out, after talks that new PM Tsipras says were unreasonable and therefore justify his refusal to pay debts which he deems unfair.

OPTION 1 Greece might opt to leave the euro if talks break down. The parliament in Athens then backs new laws bringing back the drachma. A devaluation effectively wipes out most Greek debt. On the downside, imports become more expensive and inflation takes off. Most of the nation’s wealth is wiped out. But exports become more competitive and tourists pour in, briguing down unemployment.

OPTION 2 Greece announces that it intends to stay in the euro, but not to pay all of its debt. One official at a gathering of European finance ministers in Brussels said prime minister Alexis Tsipras had “tied himself to the mast of confrontation” through his new political alliance. This leads to tough decisions for Brussels ...

Will Syriza stick to its debt reduction policy in government?

OPTION 2 Syriza has formed a government with the Greek Independence party, a hardline group of MPs who want to quit the euro, making a climbdown by Athens less likely. But the coalition may not last. Other parties available for coalition are more moderate and would limit Syriza’s room for manoeuvre.

OPTION 1 Debt reduction or bust is the opening gambit of the Syriza government. Angela Merkel and a host of other leaders have already said no, but a standoff leaves the European commission to propose alternatives that come near the savings Greece could expect from a debt writedown.